High-end filmmaking has long been a discipline in which huge efforts were made to put the most capable equipment in the most interesting places, but ever since crews hauled 65mm into the deep desert for Lawrence of Arabia, ambitious cinematographers have pushed for smaller, easier gear.

Better film stocks and digital cameras helped cinematographers in their pursuit for lightweight filmmaking, but the dimensions of lenses were fixed by the laws of physics until computer-aided optical design – and much faster cameras – made lighter options possible.

Those lightweight options became particularly relevant to Xavier Dolléans AFC on Rivages, directed by David Hourrègue for France TV. Planning an ambitious slate of photography on and under the sea, Dolléans needed equipment to suit a variety of underwater housings and surface grip equipment. “We wanted to be full frame to have a shallow depth of field. We shot in, below and above the sea, on a crane running with a heavy head, but mostly with a Ronin as a remote head. We shot in a water tank studio and in many different setups.”

Traditional approaches, Dolleans points out, could not work. “I was looking for full frame anamorphic so the only thing we could do was go for Atlas Mercury. They are well-engineered for the camera assistant, and we needed them to be available in quantity for two cameras. They’re not old lenses, but they have the old look.”

Horizons of compact full-frame anamorphics have broadened, Dolléans says, even since the end of 2023, though those new options are not always without compromise. “Now you have more options with full-frame anamorphic but [then] it was not so obvious. Now you have many lenses from new manufacturers – sometimes you don’t know the quality, the build. Sometimes it’s looking more like a still photo lens, but with Atlas I liked the look and build.”

Dolléans paired his Mercury lenses with the Sony Venice, using the Rialto option to separate the camera head from the body. “Using the Rialto with Mercury lenses, it’s the smallest full frame anamorphic possible. It’s very lightweight and you’re shooting some of the best formats you can expect. It was liberating shooting with a very small camera with such a wonderful quality.”

While that combination served much of Rivages’ photography well, Dolléans knew such a complex shoot demanded more flexibility. “We needed anamorphic zoom lenses, to match the look of the Mercury we were supposed to shoot in the sea, when we didn’t have time to change lenses. I used the Angénieux 56-152mm Optimo Anamorphic. That was – for an anamorphic zoom – not so lightweight, but lighter compared to other options.”

Journey of discovery

While technology has not so far found a way to alter optical physics, it can offer workarounds. “The Angénieux is a rear anamorphic, so you don’t have so much anamorphic look. I put in an orange streak filter to emulate the look of the Mercury. The match was not perfect, but there was a similar nature of orange flare. And [post production] was using Baselight, so I shot some Mercury flares on black background as a reference, and we mimicked them with some Baselight tools.”

Despite the excellence of the Rialto-Atlas combination, considerations beyond sheer bulk pushed Dolléans toward another approach for his underwater work. “We had to stick to spherical to go underwater, for many reasons. When you go underwater you lose so much definition – you have so much debris in the water, you lose colour, you lose everything. We shot with Venice 1 under water and Venice 2 above the water for economic and practical reasons, but the underwater cinematographer told me anamorphic below water is not so beautiful, and quickly you lose definition if your lens is not perfect at the sides. Nobody’s going to notice the difference because it’s so different to shooting above water anyway.”

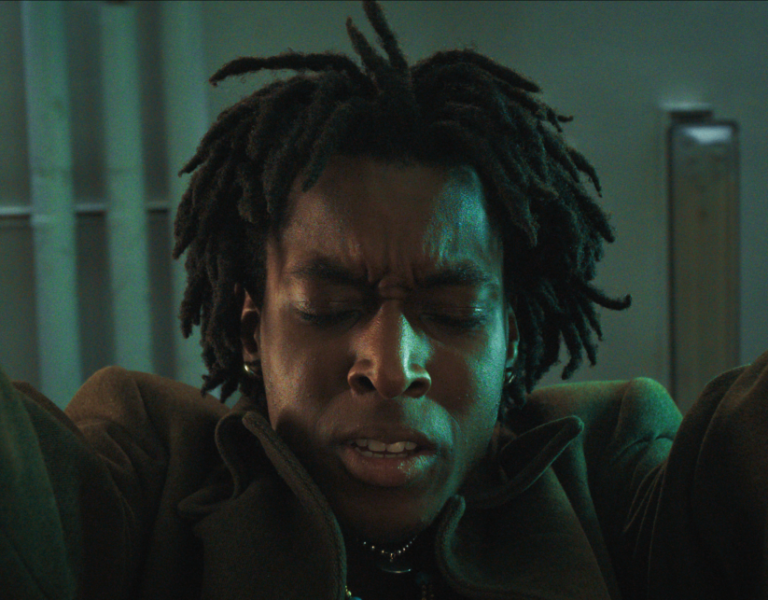

Dolléans’ need to maintain proper colour rendering had a specific story point. “The monster emits magenta light. We shot it in a water tank in Belgium. I had a choice to use the anamorphic lens or the Angénieux 22-60mm EZ-2 zoom. We did a test with the anamorphic Mercury when the camera operator was five metres from the light box and it was fine, but when he was 15 metres from the light box below the water, no more colour. At some point we switched to spherical and suddenly the colour appeared again. The coating affected the way the light is transmitted by the lens so we stuck with this more perfect, less interesting lens. It was an interesting journey mixing everything and finding a balance.”

Innovation and experimentation

The need for lightweight equipment is not limited solely to the complexities of underwater shooting, as Dolléans found on Marinette, a biopic covering Marinette Pichon, the first French woman to become part of the American professional soccer league.

After exploring options that would make it possible to run behind a footballer on a soccer field, Dolléans returned to Atlas, this time opting for the Orion series. “It was the only option that would allow working with many sets of lenses, lightweight, with an anamorphic look. If you want two full sets of lenses, you have to go, most of the time, to recent anamorphics, and if you look for some character from your lenses this is difficult. It’s great that manufacturers are trying to create new lenses, not so well corrected spherical or anamorphic formulas, and to offer some lightweight options. I’m happy to live in this time of experimentation with lenses, sizes, formats and framelines, coatings that you can customise.”

What helps, Dolléans says, is that the capability of modern cameras has brought more practicability to older, slower lenses, or lenses which work best at narrower apertures. “I think speed is not an issue anymore, thanks to the sensors we have now. I pushed the Venice to 6000 ISO with good post production. On Venice 2, you switch to the second base ISO, which is 3200, and you have a good dynamic in the blacks and the whites. I chose the camera on that project mainly for that reason. We knew we were going to shoot a lot at night and dusk.”

Interestingly, Rivages and Marinette allowed Dolléans to compare two lens sets from a single manufacturer which had both been chosen with portability in mind. “The Mercurys open up to a T2.2, which is very useful at night. The definition stays at the centre of the frame. When you are working with Orion, technically they open up to 2, but an Orion at 2.8 is soft. With the Mercury the centre of the frame is still very precise. I was shooting between 2.2 and 2.8 with Mercury.”

Access to those options is one benefit of the modern world. The conclusion Dolléans leans toward, however, is to recognise a technological collaboration including camera and post-production technique. “When you do [high ISO], you bring some texture,” he accepts, “but you know you have some people behind you. Every time I finish a project, I’m trying to test new things, new lenses, new codecs, new formats. I’m trying to test many things. When you test Cooke anamorphics, full frame, it’s very heavy and cumbersome but for some projects it’s working very well. For other projects, not so much.”

“The lens is just pieces of glass in a metal cylinder, but around this is the sensor technology, and the post-production technology, and you have this elastic post production capability where you can mix your lenses.” The result, Dolléans concludes, is a far vaster range of options than has ever existed. “This is a lot more creative than 20 years ago when I started. Anamorphic was limited, expensive and heavy and the maximum stop was something like 2.8 or 4. Now, with the sensors and the revolution of lenses, lenses are more and more interesting to explore.”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes